Unit 7 continuation: Machine Learning with Decision trees and Random Forests

This is an OLDER SEMESTER.

Go to current semester

This is a continuation of Unit 7.

Fitting, over-fitting, generalization, and model choice

When we develop or train machine learning models we use the seen data. We often assume it is i.i.d. data and if we have reason to believe it isn't we shuffle it, or collect it in a way where it is likely to be i.i.d.

We then can choose a model to fit the data. And we want to "fit the data well". This sounds sensible, but is clearly subject to abuse. We can effectively have a model that fits every data point exactly!

Here is one example of this where our data consists of $(x,y)$ pairs and we use a Vandermonde Matrix to fit a polynomial that goes through each training point exactly. The example also has a linear fit using the pseudo-inverse. Which model is better?

As you answer this question, consider also the fact that there is unseen data which we don't get to see as we develop the model (red points in the curve).

using Plots, LinearAlgebra x_seen = [-2, 3, 5, 6, 12, 14] y_seen = [7, 2, 9, 3, 12, 3] n = length(x_seen) x_unseen = [15, -1, 5.5, 7.8] y_unseen = [3.5, 6, 8.7, 10.4] # Polynomial interpolation to fit exactly each point V = [x_seen[i+1]^(j) for i in 0:n-1, j in 0:n-1] c = V \ y_seen f1(x) = c'*[x^i for i in 0:n-1] #Linear fit A = [ones(n) x_seen] β = pinv(A)*y_seen beta0, beta1 = 4.58, 0.17 f2(x) =β'*[1,x] xGrid = -5:0.01:20 plot(xGrid,f1.(xGrid), c=:blue, label="Exact Polynomial fit") plot!(xGrid,f2.(xGrid),c=:red, label="Linear model") scatter!(x_seen,y_seen, c=:black, shape=:diamond, ms=6,label="Seen Data points") scatter!(x_unseen,y_unseen, c=:red, shape=:circle, ms=6, label="Unseen Data points", xlims=(-5,20), ylims=(-50,50), xlabel = "x", ylabel = "y")

So in general it is obvious that a model that "fits our data exactly" is typically not the best model. Much of machine learning theory attempts to quantify this tradeoff between an over-fit of the training data and a good model. Sometimes this falls under the title of the Bias Variance tradeoff in machine learning theory where the bias of a model (or estimator) is associated with under-fitting and the variance of a model is associated with over-fitting.

We don't get into the full mathematical details of over-fitting/under-fitting, generalization error and the bias variance tradeoff. A good introductory resource for the theory of this is the book Data Science and Machine Learning: Mathematical and Statistical Methods . A much lighter book is The hundred page machine learning book.

Handling the data

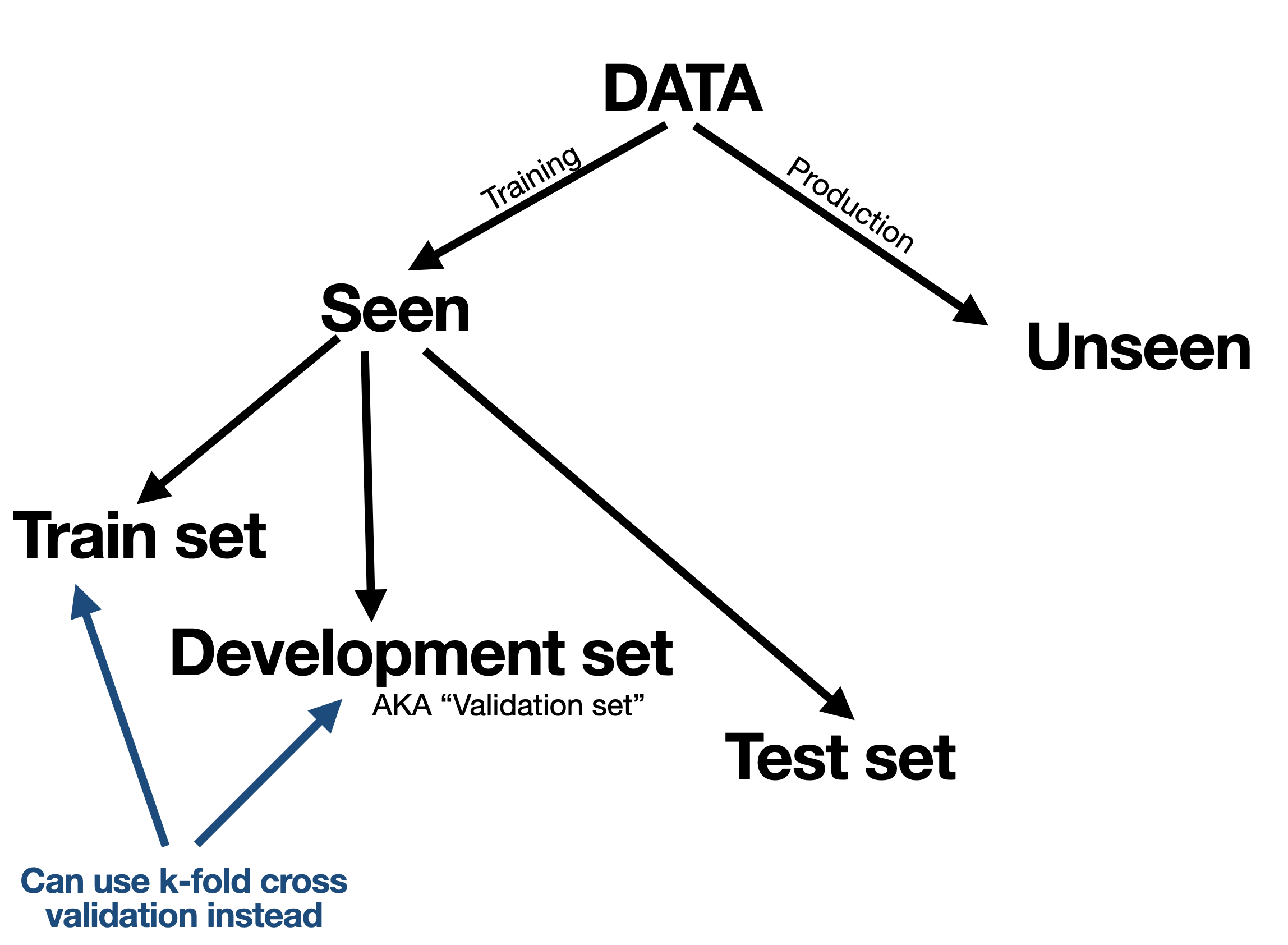

In view of over-fitting and under-fitting considerations, a first thing to consider is how to handle the data. Here is an overview:

We typically split our available (seen) data into a training set and test set. The idea of the test set is to use it only once to mimic a situation where it is unseen. However the training data is further split into a training set (this word used twice) and a validation set (also known as development set) where we can tune and calibrate the model again and again on the training data while seeing how it performs on the validation set.

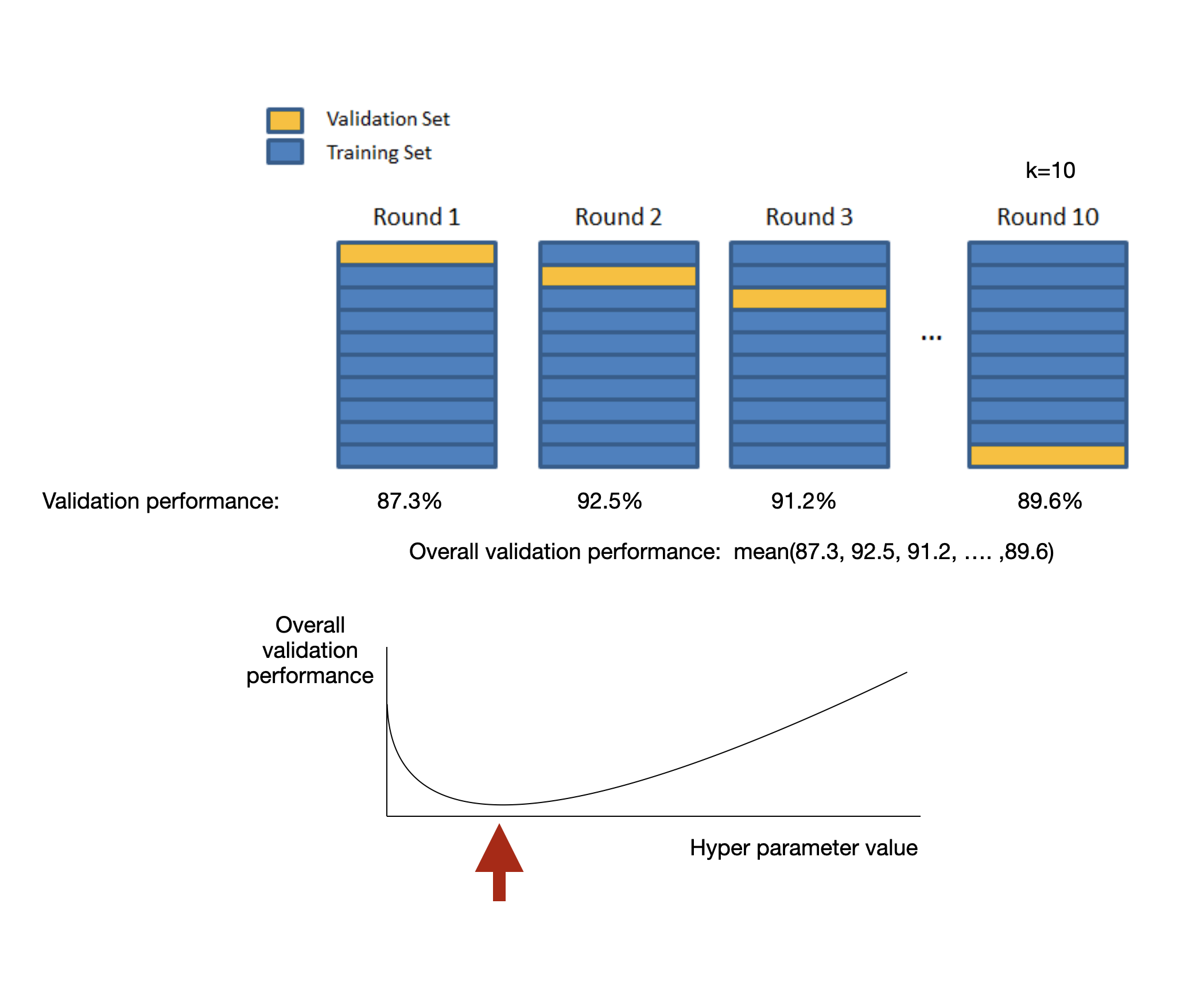

Sometimes instead of using a validation set we can do k-fold cross validation or some variant of it.

In any case, our purpose fo the training/validation/cross-validation data is to select the right model, train the model, and tune hyper-parameters.

Tree based models

We now focus on tree based models. Decision trees for machine learning have a long history a nd constitute a set of models that is still very much in use today. These models are enhanced with Random forest models which use a general machine learning technique Ensemble Method, or bagging also known as bootstrap aggregation.

We first introduce and explore basics of decision trees both for regression and classification. We then see that on their own, decision trees are somewhat limited because they can easily over-fit. We then consider random forests which constitute a much more versatile algorithm.

Basic Decision trees

To illustrate we'll first consider a classification problem with $d=2$ features and $k=3$. For simplicity we generate synthetic data via a mixture of bi-variate normals.

using Distributions, Random, LaTeXStrings, Plots Random.seed!(1) d, k = 2, 3 #d features and k label types make_data(class1 = 50, class2 = 30, class3 = 20) = (vcat( rand(MvNormal([1,1],[3 0.7; 0.7 3]), class1)', rand(MvNormal([4,2],[2.5 -0.7; -0.7 2.5]), class2)', rand(MvNormal([2,4],[2 0.7; 0.7 2]), class3)') , vcat(fill(1,class1), fill(2,class2), fill(3,class3)) ) X, y = make_data() n = length(y) label_colors = [:red :green :blue] xlim, ylim = (-3,8),(-3,8) #We'll plot points again below, so putting it in in a function plot_points(plt_function, X, y) = plt_function(X[:,1], X[:,2], c = label_colors, ms=5, group = y, xlabel=L"X_1", ylabel=L"X_2", xlim = xlim, ylim = ylim,legend=:topleft) plot_points(scatter, X, y)

A decision tree classifier splits the input space (in this case $\mathbb{R}^2$) into disjoint regions based on a sequence of decision rules. We illustrate this directly using code. For example, a node in such a decision tree can be implemented with nodes such as:

mutable struct DecisionTreeNode #This is either a class decision (1, 2, or 3 when there are three classes) #or a function that returns false for "left" and true for "right" decision::Union{Int, Function} #Children lchild::Union{DecisionTreeNode, Nothing} rchild::Union{DecisionTreeNode, Nothing} end

Lets first manually construct such a tree with (somewhat) arbitrary cut-offs, starting at first with a single decision based on $X_1$:

manual_tree = DecisionTreeNode( (x)->x[1]<2, #This is the decision rule DecisionTreeNode(1, nothing,nothing), DecisionTreeNode(2, nothing,nothing));

Now prediction can be done by recursively running down the tree:

function predict(tree::DecisionTreeNode, features::Vector{Float64}) isa(tree.decision, Int) && return tree.decision if tree.decision(features) return predict(tree.lchild, features) else return predict(tree.rchild, features) end end;

Here is our (simple) tree's prediction visually:

tree_accuracy(tree, X, y) = mean(predict(tree, X[i,:]) == y[i] for i in 1:size(X)[1]) x1_grid, x2_grid = xlim[1]:0.005:xlim[2], ylim[1]:0.005:ylim[2] ccol = cgrad([RGB(1,0,0), RGB(0,1,0), RGB(0,0,1)]) function plot_decision(tree, X, y) contour(x1_grid, x2_grid, (x1,x2)->predict(tree,[x1,x2]), f=true, nlev=3, c=ccol, legend = :none, title = "Training Accuracy = $(tree_accuracy(tree, X, y))") plot_points(scatter!, X, y) end plot_decision(manual_tree, X, y)

Now we can add more rules by adding more nodes (let's still do this manually):

#Split the right child manual_tree.rchild.decision = (x)->x[2]>4 manual_tree.rchild.lchild = DecisionTreeNode(3,nothing,nothing) manual_tree.rchild.rchild = DecisionTreeNode(2,nothing,nothing) plot_decision(manual_tree, X, y)

We can also print the tree (similar code appeared for heaps in the previous unit):

function Base.show(io::IO, node::DecisionTreeNode, this_prefix = "", subtree_prefix = "") print(io, "\n", this_prefix, node.lchild === nothing ? "── " : "─┬ ") show(io, node.decision) # print children if node.lchild !== nothing if node.rchild !== nothing show(io, node.lchild, "$(subtree_prefix) ├", "$(subtree_prefix) │") else show(io, node.lchild, "$(subtree_prefix) └", "$(subtree_prefix) ") end end if node.rchild !== nothing show(io, node.rchild, "$(subtree_prefix) └", "$(subtree_prefix) ") end end manual_tree

─┬ var"#51#52"() ├── 1 └─┬ var"#57#58"() ├── 3 └── 2

With the above printout since decision rules are functions they don't "display nicely" but with a better implementation this can be overcome.

Here is one more rule:

#split the right child manual_tree.lchild.decision = (x)-> x[2]>1.9 manual_tree.lchild.lchild = DecisionTreeNode(3,nothing,nothing) manual_tree.lchild.rchild = DecisionTreeNode(1,nothing,nothing) manual_tree

─┬ var"#51#52"() ├─┬ var"#59#60"() │ ├── 3 │ └── 1 └─┬ var"#57#58"() ├── 3 └── 2

plot_decision(manual_tree, X, y)

You can now see that with more and more additions to the tree the training accuracy can increase since in principle, each observation can eventually lie in the correct spot. However be careful we are over-fitting!. You can in principle mitigate over-fitting by finding the right balance for how deep a tree should be using for example cross validation. But below, we'll use a more general technique called random forests.

Still, before we deal with random forests that improve accuracy and allow to mitigate over-fitting, lets see one way to build the decision tree. There are multiple ways and methods, we will focus on one method based on a greedy algorithm. This is sometimes called a "top-down" construction.

For this we'll use a slightly different struct for each node that doesn't only keep the decision rule, but also keeps the data available up to that node. We'll also keep the depth of the node in each node.

mutable struct DecisionTreeNodeWithData #The data available to the node X::Matrix{Float64} y::Vector{Int} #This is either a class decision (1, 2, or 3 when there are three classes) #or a function that returns false for "left" and true for "right" #or nothing if the node isn't initialized yet decision::Union{Int, Function, Nothing} #Children lchild::Union{DecisionTreeNodeWithData, Nothing} rchild::Union{DecisionTreeNodeWithData, Nothing} #Counts the depth of the tree depth::Int end

#make an empty tree init_tree(X, y) = DecisionTreeNodeWithData(X, y, nothing, nothing, nothing, 1); auto_split_tree = init_tree(X, y)

── "Splitting rule"

Now this splitting rule function is the most important function since it takes a node and decides how to split it. Here decision tree algorithms could use different measures, sometimes called impurity functions. In our case (and so far focusing on classification) we'll decide to split based on the feature and value that minimizes.

\[ \frac{1}{\text{num left}} \sum_{\text{left}} {\mathbf 1}\{ \text{mismatch in prediction} \} + \frac{1}{\text{num right}} \sum_{\text{right}} {\mathbf 1}\{ \text{mismatch in prediction} \}. \]

using StatsBase: mode #used here for finding the most common label function find_splitting_rule(node::DecisionTreeNodeWithData) X, y = node.X, node.y n, d = size(X) loss, τ, feature = Inf, NaN, -1 pred_left_choice, pred_right_choice = -1, -1 final_left_bits = BitVector() #Loop over all features for j = 1:d #Loop over all observations for i in 1:n τ_candidate = X[i,j] left_bits = X[:,j] .≤ τ_candidate right_bits = .!left_bits pred_left, pred_right = 0, 0 (sum(left_bits) == 0 || sum(left_bits) == n) && continue pred_left = mode(y[left_bits]) pred_right = mode(y[right_bits]) new_loss = mean(y[left_bits] .!= pred_left) + mean(y[right_bits] .!= pred_right) #if found a better split than previously then retain it if new_loss < loss final_left_bits = left_bits pred_left_choice = pred_left pred_right_choice = pred_right feature = j τ = τ_candidate loss = new_loss end end end return (rule = (x)->x[feature] ≤ τ, left_value = pred_left_choice, right_value = pred_right_choice, left_bits = final_left_bits) end;

Here is prediction function for this type just like above (only written more tightly):

function predict(tree::DecisionTreeNodeWithData, features::Vector{Float64}) isa(tree.decision, Int) && return tree.decision tree.decision(features) && return predict(tree.lchild, features) return predict(tree.rchild, features) end;

Here is a printing function, also just like above:

function Base.show(io::IO, node::DecisionTreeNodeWithData, this_prefix = "", subtree_prefix = "") print(io, "\n", this_prefix, node.lchild === nothing ? "── " : "─┬ ") show(io, isa(node.decision,Int) ? node.decision : "Splitting rule") if node.lchild !== nothing if node.rchild !== nothing show(io, node.lchild, "$(subtree_prefix) ├", "$(subtree_prefix) │") else show(io, node.lchild, "$(subtree_prefix) └", "$(subtree_prefix) ") end end node.rchild !== nothing && show(io, node.rchild, "$(subtree_prefix) └", "$(subtree_prefix) ") end;

We can then do this recursively. But careful if max_depth is infinity` then this is a seriously over-fitted tree because it exactly describes the the training data:

function build_tree!(node::DecisionTreeNodeWithData; max_depth = Inf)::Nothing length(node.y) == 1 && return length(unique(node.y)) ≤ 1 && return (node.depth ≥ max_depth) && return splitting_result = find_splitting_rule(node) right_bits = .!splitting_result.left_bits #.! flips the bits node.decision = splitting_result.rule node.lchild = DecisionTreeNodeWithData( node.X[splitting_result.left_bits,:], node.y[splitting_result.left_bits], splitting_result.left_value, nothing, nothing, node.depth + 1) node.rchild = DecisionTreeNodeWithData( node.X[right_bits,:], node.y[right_bits], splitting_result.right_value, nothing, nothing, node.depth + 1); build_tree!(node.lchild, max_depth=max_depth) build_tree!(node.rchild, max_depth=max_depth) end;

Let's build a tree:

auto_split_tree = init_tree(X, y); build_tree!(auto_split_tree) plot_decision(auto_split_tree, X, y)

Let's count how many nodes we have (this is called "walking the tree"):

function num_nodes(node::DecisionTreeNodeWithData; count = 0) count += 1 node.lchild != nothing && (count = num_nodes(node.lchild; count = count)) node.rchild != nothing && (count = num_nodes(node.rchild; count = count)) return count end num_nodes(auto_split_tree)

139

Similarly we can look at the depth of the tree (this implementation use the fact here that every node has a depth field):

function depth(node::DecisionTreeNodeWithData; max_depth = 1) (node.lchild == nothing && node.rchild == nothing) && return node.depth (node.lchild != nothing && node.rchild == nothing) && return max(max_depth, depth(node.lchild)) (node.lchild == nothing && node.rchild != nothing) && return max(max_depth, depth(node.rchild)) return max(max_depth, depth(node.lchild), depth(node.rchild)) end depth(auto_split_tree)

70

Instead lets incrementally build trees with more depth

for d = 2:100 tree = init_tree(X, y) build_tree!(tree, max_depth = d) tree_summary = (max_depth = d, actual_depth = depth(tree), num = num_nodes(tree), acc = tree_accuracy(tree, X, y)) println(tree_summary) end

(max_depth = 2, actual_depth = 2, num = 3, acc = 0.59) (max_depth = 3, actual_depth = 3, num = 5, acc = 0.65) (max_depth = 4, actual_depth = 4, num = 7, acc = 0.66) (max_depth = 5, actual_depth = 5, num = 9, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 6, actual_depth = 6, num = 11, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 7, actual_depth = 7, num = 13, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 8, actual_depth = 8, num = 15, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 9, actual_depth = 9, num = 17, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 10, actual_depth = 10, num = 19, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 11, actual_depth = 11, num = 21, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 12, actual_depth = 12, num = 23, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 13, actual_depth = 13, num = 25, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 14, actual_depth = 14, num = 27, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 15, actual_depth = 15, num = 29, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 16, actual_depth = 16, num = 31, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 17, actual_depth = 17, num = 33, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 18, actual_depth = 18, num = 35, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 19, actual_depth = 19, num = 37, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 20, actual_depth = 20, num = 39, acc = 0.71) (max_depth = 21, actual_depth = 21, num = 41, acc = 0.72) (max_depth = 22, actual_depth = 22, num = 43, acc = 0.72) (max_depth = 23, actual_depth = 23, num = 45, acc = 0.72) (max_depth = 24, actual_depth = 24, num = 47, acc = 0.72) (max_depth = 25, actual_depth = 25, num = 49, acc = 0.72) (max_depth = 26, actual_depth = 26, num = 51, acc = 0.73) (max_depth = 27, actual_depth = 27, num = 53, acc = 0.73) (max_depth = 28, actual_depth = 28, num = 55, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 29, actual_depth = 29, num = 57, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 30, actual_depth = 30, num = 59, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 31, actual_depth = 31, num = 61, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 32, actual_depth = 32, num = 63, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 33, actual_depth = 33, num = 65, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 34, actual_depth = 34, num = 67, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 35, actual_depth = 35, num = 69, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 36, actual_depth = 36, num = 71, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 37, actual_depth = 37, num = 73, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 38, actual_depth = 38, num = 75, acc = 0.75) (max_depth = 39, actual_depth = 39, num = 77, acc = 0.76) (max_depth = 40, actual_depth = 40, num = 79, acc = 0.77) (max_depth = 41, actual_depth = 41, num = 81, acc = 0.78) (max_depth = 42, actual_depth = 42, num = 83, acc = 0.78) (max_depth = 43, actual_depth = 43, num = 85, acc = 0.79) (max_depth = 44, actual_depth = 44, num = 87, acc = 0.79) (max_depth = 45, actual_depth = 45, num = 89, acc = 0.79) (max_depth = 46, actual_depth = 46, num = 91, acc = 0.8) (max_depth = 47, actual_depth = 47, num = 93, acc = 0.82) (max_depth = 48, actual_depth = 48, num = 95, acc = 0.82) (max_depth = 49, actual_depth = 49, num = 97, acc = 0.83) (max_depth = 50, actual_depth = 50, num = 99, acc = 0.83) (max_depth = 51, actual_depth = 51, num = 101, acc = 0.84) (max_depth = 52, actual_depth = 52, num = 103, acc = 0.85) (max_depth = 53, actual_depth = 53, num = 105, acc = 0.86) (max_depth = 54, actual_depth = 54, num = 107, acc = 0.86) (max_depth = 55, actual_depth = 55, num = 109, acc = 0.88) (max_depth = 56, actual_depth = 56, num = 111, acc = 0.88) (max_depth = 57, actual_depth = 57, num = 113, acc = 0.89) (max_depth = 58, actual_depth = 58, num = 115, acc = 0.89) (max_depth = 59, actual_depth = 59, num = 117, acc = 0.89) (max_depth = 60, actual_depth = 60, num = 119, acc = 0.9) (max_depth = 61, actual_depth = 61, num = 121, acc = 0.9) (max_depth = 62, actual_depth = 62, num = 123, acc = 0.93) (max_depth = 63, actual_depth = 63, num = 125, acc = 0.95) (max_depth = 64, actual_depth = 64, num = 127, acc = 0.95) (max_depth = 65, actual_depth = 65, num = 129, acc = 0.97) (max_depth = 66, actual_depth = 66, num = 131, acc = 0.97) (max_depth = 67, actual_depth = 67, num = 133, acc = 0.97) (max_depth = 68, actual_depth = 68, num = 135, acc = 0.98) (max_depth = 69, actual_depth = 69, num = 137, acc = 0.98) (max_depth = 70, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 71, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 72, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 73, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 74, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 75, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 76, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 77, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 78, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 79, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 80, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 81, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 82, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 83, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 84, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 85, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 86, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 87, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 88, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 89, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 90, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 91, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 92, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 93, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 94, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 95, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 96, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 97, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 98, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 99, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0) (max_depth = 100, actual_depth = 70, num = 139, acc = 1.0)

Here is an animation of this:

anim = Animation() for d in union(2:3,10:5:80) tree = init_tree(X, y); build_tree!(tree, max_depth = d) plot_decision(tree, X, y) frame(anim) end gif(anim, "decision_tree.gif", fps = 1)

Now such over-fitting is obviously not good. Let's consider (an hypothetical) validation dataset in addition to the training dataset.

Random.seed!(1) X, y = make_data(100,100,100) #training dataset X_validate, y_validate = make_data(40,40,40) p_train = plot_points(scatter, X, y) plot!(p_train, title = "Training data") p_validate = plot_points(scatter, X_validate, y_validate) plot!(p_validate, title = "Validation data") plot(p_train, p_validate)

By construction, the validation data above seems similar to the training data, however as we can see fitting a decision tree with a depth of more than about $10$ decreases validation accuracy. We are over-fitting!

train_acc = Float64[] validation_acc = Float64[] for d = 2:150 tree = init_tree(X, y) build_tree!(tree, max_depth = d) push!(train_acc, tree_accuracy(tree, X, y)) push!(validation_acc, tree_accuracy(tree, X_validate, y_validate)) end plot(2:150, [train_acc validation_acc], label = ["training" "validation"], ylim =(0, 1.1), legend = :bottomleft, shape = :circle, xlabel = "Max Depth", ylabel = "Accuracy")

Trees for regression

You can use decision trees for regression instead of classification. The key idea is to use a loss that quantifies the regression error at every split. Here typically we would need a stopping rule for how deep to go. More on this is in the practical.

Dealing with categorical features

When we deal with categorical features the typical thing to do is one hot encoding. That is, if there is a categorical features with say three possible values, we will create three binary columns for this categorical feature where in each row, there is only a single $1$ in one of these columns and the other two will be $0$.

Using a package

Now that we understood the basics of decision trees, lets use a package with more versatile and optimized code. We'll use DecisionTree.jl. Another popular package is XGBoost.jl which wraps the popular XGBoost library code. In any case, when working with machine learning with Julia you will often use a framework such as MLJ. Similarly in Python the most popular choice is scikit-learn. Note that Julia also has the adapted, ScikitLearn.jl. We won't use these but rather create code directly or use DecisionTree.jl.

Back to MNIST:

using MLDatasets train_data = MLDatasets.MNIST.traindata(Float64) train_imgs = train_data[1] train_labels = train_data[2] test_data = MLDatasets.MNIST.testdata(Float64) test_imgs = test_data[1] test_labels = test_data[2]; n_train, n_test = length(train_labels), length(test_labels) y_train = train_labels y_test = test_labels X_train = vcat([vec(train_imgs[:,:,k])' for k in 1:n_train]...) X_test = vcat([vec(test_imgs[:,:,k])' for k in 1:n_test]...); size(X_train), size(X_test)

((60000, 784), (10000, 784))

Let's build a tree using the default API of DecisionTree.jl:

using DecisionTree, Statistics # set of classification parameters and respective default values # pruning_purity: purity threshold used for post-pruning (default: 1.0, no pruning) # max_depth: maximum depth of the decision tree (default: -1, no maximum) # min_samples_leaf: the minimum number of samples each leaf needs to have (default: 1) # min_samples_split: the minimum number of samples in needed for a split (default: 2) # min_purity_increase: minimum purity needed for a split (default: 0.0) # n_subfeatures: number of features to select at random (default: 0, keep all) # keyword rng: the random number generator or seed to use (default Random.GLOBAL_RNG) n_subfeatures=0; max_depth=-1; min_samples_leaf=1; min_samples_split=2 min_purity_increase=0.0; pruning_purity = 1.0; seed=3 tree_model = build_tree(y_train, X_train, n_subfeatures, max_depth, min_samples_leaf, min_samples_split, min_purity_increase; rng = seed)

Decision Tree Leaves: 3327 Depth: 22

predicted_labels = apply_tree(tree_model, X_test) accuracy = mean(predicted_labels .== y_test) println("\nPrediction accuracy (measured on test set of size $n_test): ",accuracy)

Prediction accuracy (measured on test set of size 10000): 0.886

Random forests

The idea of the random forest algorithm is to build an ensemble of trees, not just one tree. It builds on a more general idea studied in machine learning theory called "bagging". (There is also an idea of "boosting" that we don't discuss here). The general idea of bagging is to create a model,

\[ \hat{f}(x) = \frac{1}{b} \sum_{i=1}^b \hat{f}_i(x), \]

where each $\hat{f}_i(\cdot)$ is a model trained on a random subset of the data. The way the random subset is selected is by choosing random observations from the data with replacement. So the data used to train each $\hat{f}_i(\cdot)$ is the original data, but typically with some observations missing and some observations repeated. This randomization yields better performance.

The above averaging is for regression models and in classification a majority vote can be taken.

Random forests use the idea of bagging but also go beyond it: Each time that a decision tree $\hat{f}_i(\cdot)$ is trained, it isn't only trained on bagged observations, but is also trained with only a small random set of features available. It is typical (and has some supporting theory) to choose $\sqrt{d}$ random features in cases where there are $d$ features available.

So if the data available for training is the the vector $y$ and the $n\times d$ matrix $X$, then in a random forest each tree is trained with some random $n \times \lceil \sqrt{d}\rceil$ matrix $\tilde{X}$ which has rows randomly selected from the original $X$ with repetitions, and columns selected randomly from the original $X$ as well. The combination of many (or several) such trees then yields better prediction performance without danger of over-fitting.

Without getting into all the details, here is the heart of the random forest implementation (for classification) taken from DecisionTree.jl. This is from the file https://github.com/bensadeghi/DecisionTree.jl/blob/master/src/classification/main.jl. Note that the build_tree function already implements selecting a random features.

This is also an example to see some multi-threaded code. A concept we completely didn't discuss in this course:

function build_forest(

labels :: AbstractVector{T},

features :: AbstractMatrix{S},

n_subfeatures = -1,

n_trees = 10,

partial_sampling = 0.7,

max_depth = -1,

min_samples_leaf = 1,

min_samples_split = 2,

min_purity_increase = 0.0;

rng = Random.GLOBAL_RNG) where {S, T}

if n_trees < 1

throw("the number of trees must be >= 1")

end

if !(0.0 < partial_sampling <= 1.0)

throw("partial_sampling must be in the range (0,1]")

end

if n_subfeatures == -1

n_features = size(features, 2)

n_subfeatures = round(Int, sqrt(n_features))

end

t_samples = length(labels)

n_samples = floor(Int, partial_sampling * t_samples)

forest = Vector{LeafOrNode{S, T}}(undef, n_trees)

entropy_terms = util.compute_entropy_terms(n_samples)

loss = (ns, n) -> util.entropy(ns, n, entropy_terms)

if rng isa Random.AbstractRNG

Threads.@threads for i in 1:n_trees

inds = rand(rng, 1:t_samples, n_samples)

forest[i] = build_tree(

labels[inds],

features[inds,:],

n_subfeatures,

max_depth,

min_samples_leaf,

min_samples_split,

min_purity_increase,

loss = loss,

rng = rng)

end

elseif rng isa Integer # each thread gets its own seeded rng

Threads.@threads for i in 1:n_trees

Random.seed!(rng + i)

inds = rand(1:t_samples, n_samples)

forest[i] = build_tree(

labels[inds],

features[inds,:],

n_subfeatures,

max_depth,

min_samples_leaf,

min_samples_split,

min_purity_increase,

loss = loss)

end

else

throw("rng must of be type Integer or Random.AbstractRNG")

end

return Ensemble{S, T}(forest)

end

function apply_forest(forest::Ensemble{S, T}, features::AbstractVector{S}) where {S, T}

n_trees = length(forest)

votes = Array{T}(undef, n_trees)

for i in 1:n_trees

votes[i] = apply_tree(forest.trees[i], features)

end

if T <: Float64

return mean(votes)

else

return majority_vote(votes)

end

endWith this, we have touched only the tip of the iceberg in terms of machine learning models. However we hope it is clear that the software component of machine learning is a central one: executing machine learning effectively requires solid coding skills. Other aspects dealing with the mathematics of machine learning can be learned in STAT3006, STAT3007, and other UQ courses. Enjoy.